Natural product biosynthesis 1. Part 1

Published:

Introduction

There are upwards of 10^5 natural products, the majority of which are synthesised from simple building blocks [1]. These precursors are often compounds with a low diversity of atoms (mostly C, H and O) which can assemble into complex molecules through simple biosythetic routes. Despite appearing ‘simple’, these reactions are often challenging to synthetically perform because of their slow kinetics under standard laboratory conditions. Not only do biological enzymes funnel precursors down a shute of otherwise thermodynamically impossible reaction routes - such as hydride transfers and intramolecular cyclisations - they also exhibit exquisite stereoselectivity. Such perfectly executed catalysis is essential when the number of reaction steps becomes large - as is the case for the synthesis of larger and more complex biological compounds. An understanding of these biological mechanisms is thus important from a synthetic chemistry perspective and for exploiting biological pathways to generate novel natural products.

This post will describe polyketide synthases (PKSs). These are large megasynthases (>1.1 MDa), majorily found in fungi, that are arranged in modular assembly lines. Each module defines a new building block to be joined onto the growing compound and is modular in that different enzymes can be inserted into the assembly line to further decorate the compound with greater functionality e.g hydroxyl, methoxymethyl and glycosylation groups. Throughout this post I attempt to mantain a theme of the emergence of complexity through simple and repetitive mechanisms.

General biological mechanisms

Mechanisms covered:

- Addition reactions e.g. nucleophillic and electrophillic

- Condensation and hydrolysis reactions e.g. aldol and claisen condensations

- Elimination and isomerisation reactions e.g. enolisation and dehydrations

Enolisation

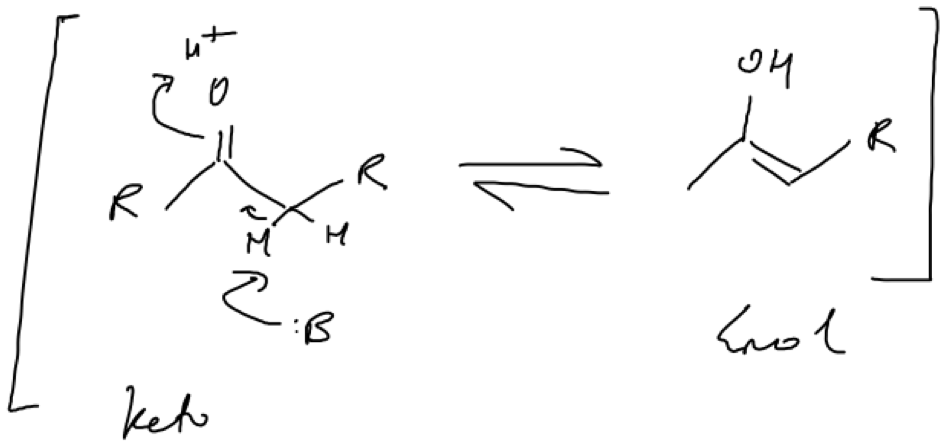

Isomerisation involves a rearangment that leaves the overall molecular weight of a compound unaltered. Enolisation (a type of tautomerisation involving proton transfers) is a type of isomerisation that occurs frequently in biochemistry and involves the interconversion between a ketone and an enol (Fig. 1). Because the two are in equilibrium, favouring the production of one can drive reactions in the forward or reverse direction. In PKSs, enolisations often generate aromatic rings from cyclical chains.

Figure 1. Example of an enolisation mechanism. A base abstracts a proton which results in a pair of electrons gravitating towards the delta positive carbon of the carbonyl group in the form of a double bond. This repels electrons within the carbonyl group to accept a proton in order to stabilise its growing negative charge.

Figure 1. Example of an enolisation mechanism. A base abstracts a proton which results in a pair of electrons gravitating towards the delta positive carbon of the carbonyl group in the form of a double bond. This repels electrons within the carbonyl group to accept a proton in order to stabilise its growing negative charge.

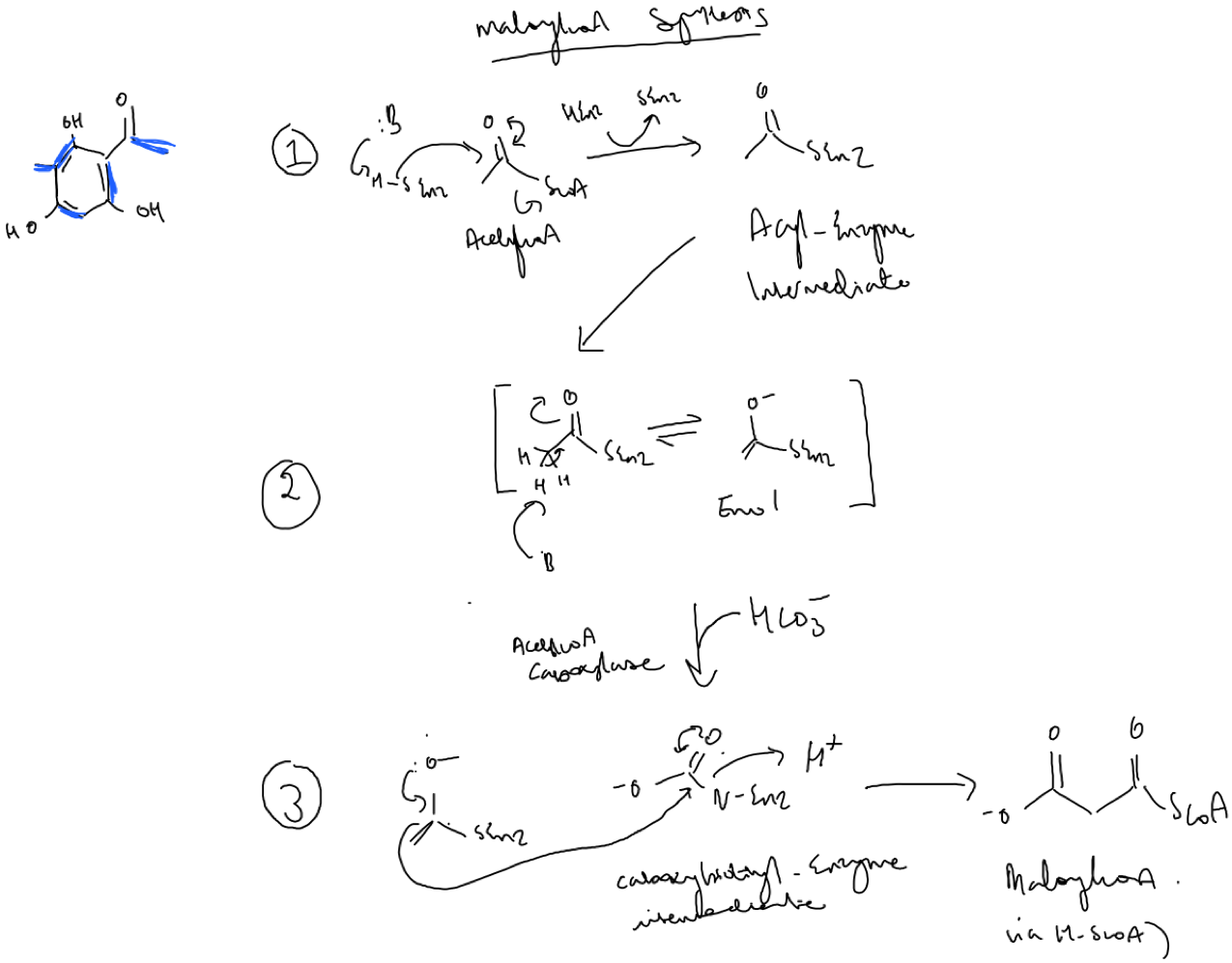

Claisen condensation

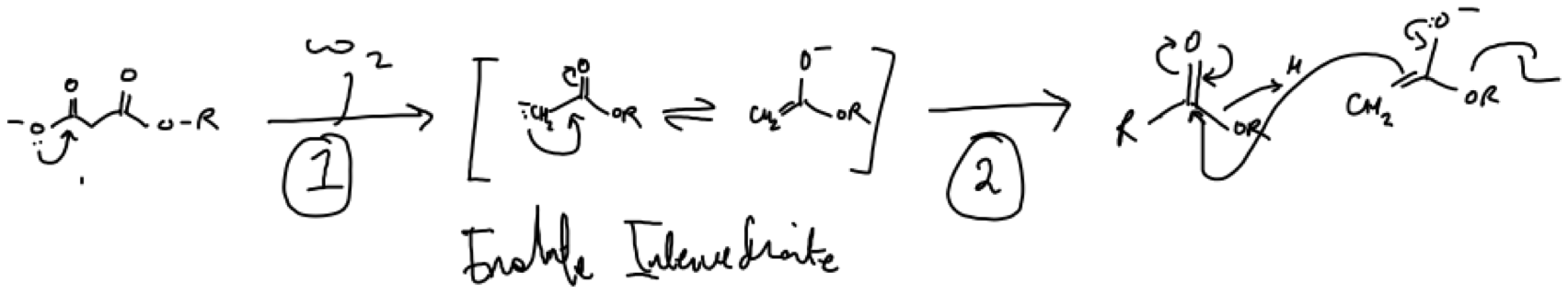

A claisen condensation involves the condensation of esters. Decarboxylative driven condensations by decarboxylases are common. Rather than writing this mechanism in one go I often find it easier to visualise an overview of a mechanism by digesting it into steps where I’m able to track the movement of electrons. The ester reactants in Fig.2 may be activated at an enzymes active site through formation of a thioester (sulfur is a stronger nucleophile than oxygen).

Figure 2. Example of a claisen condensation between two esters. (1) Loss of CO2 drives the reaction forward by forming an enolate ion. (2) This creates a double bond that acts as a nucleophile to attack the delta carbon of the carbonyl group. (3) If there is a strong nucleophile bound to the carbonyl this will be expelled via an enolate intermediate.

Figure 2. Example of a claisen condensation between two esters. (1) Loss of CO2 drives the reaction forward by forming an enolate ion. (2) This creates a double bond that acts as a nucleophile to attack the delta carbon of the carbonyl group. (3) If there is a strong nucleophile bound to the carbonyl this will be expelled via an enolate intermediate.

Nucleophillic acyl substitution reactions

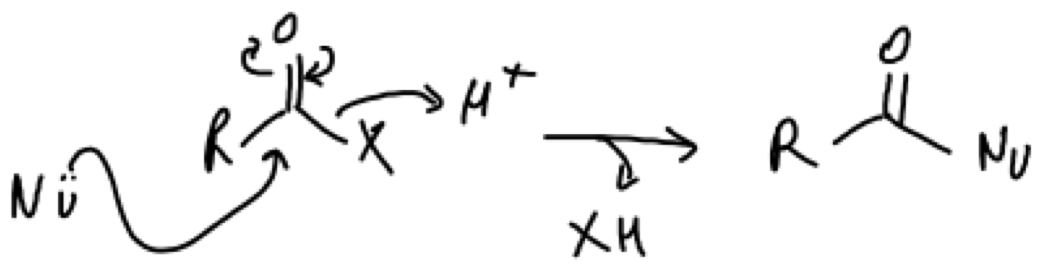

Nucleophillic acyl subsitution reactions involve a nucleophile attacking a carbonyl group to generate a R-CONucleophile (Fig.3). The reaction largely depends on the stability of the carbonyl group (Figure 2). For instance, amides are the least reactive because resonance stabilisation makes NH2 a poor leaving group, whilst acyl phosphates are very reactive. Furthermore, physiologically resident divalent cations (Mg2+) will further stabilise the negatively charged phosphate (PO42-) to increase its reactivity as a leaving group.

Figure 3. Example of a nucleophillic acyl substitution mechanism. A nucleophile attacks the carbonyl group with the subsequent movement of electrons within the carbonyl group expelling the weaker leaving group (X).

Figure 3. Example of a nucleophillic acyl substitution mechanism. A nucleophile attacks the carbonyl group with the subsequent movement of electrons within the carbonyl group expelling the weaker leaving group (X).

There can be two types of nucleophillic substitution reactions: (i) SN1 and (ii) SN2. These are named based on the rate limiting step of the reaction. In SN1 reactions the rate determining step is the loss of the leaving group (which in this case is often strong e.g. diphosphates). Once the leaving group is lost a, often weak, nucleophile can attack the carbocation. In SN2 reactions the rate is dependent on the concentration of the substrate and nucleophile. The nuclephile attacks furthest away from the leaving group (backside) in a single step reaction. This can result in inversion of the stereocentre if a chiral carbon is the recipient of the attack.

Elimination

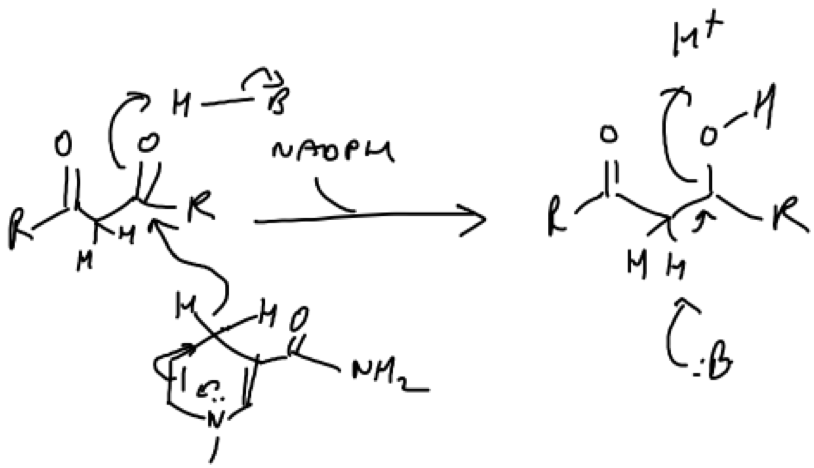

Elimination reactions such as dehydrations are common in biochemistry and often proceed by an E1cb mechanism (Fig.4). This is favoured under basic conditions and involves a poor leaving group (C=0/O-R). If there are acidic hydrogens present, which lie between strong electron withdrawing groups, this can increase the reactivity of the leaving group. The most acidic hydrogens would be those situated between two carboxylic acid groups e.g. those in a dicarboxylic acid, because they would have a strong tendency to be lost as H+ in order to stabilise the carbonyls growing negative charge.

Figure 4. Example of an elimination mechanism. The carbonyl is a poor leaving group because of its double bond. Protonation via a nucleophillic addition reaction involving NADPH/NADH as the reductant (a hydride ion is the nucleophile) could oxidise the carbonyl to an alcohol to increase its reactivity. A base catalysed reaction could then proceed involving the loss of water and the subsequent regeneration of the base by bulk solvent. The base may be a basic residue of an enzymes active site e.g. histidine, arginine or lysine (They are basic residues because they are all positively charged at physiological pH). Histidine is especially common in biological mechanisms because it can readily interconvert between neutral and +1 charged, making it a good catalyst.

Figure 4. Example of an elimination mechanism. The carbonyl is a poor leaving group because of its double bond. Protonation via a nucleophillic addition reaction involving NADPH/NADH as the reductant (a hydride ion is the nucleophile) could oxidise the carbonyl to an alcohol to increase its reactivity. A base catalysed reaction could then proceed involving the loss of water and the subsequent regeneration of the base by bulk solvent. The base may be a basic residue of an enzymes active site e.g. histidine, arginine or lysine (They are basic residues because they are all positively charged at physiological pH). Histidine is especially common in biological mechanisms because it can readily interconvert between neutral and +1 charged, making it a good catalyst.

Epoxidations

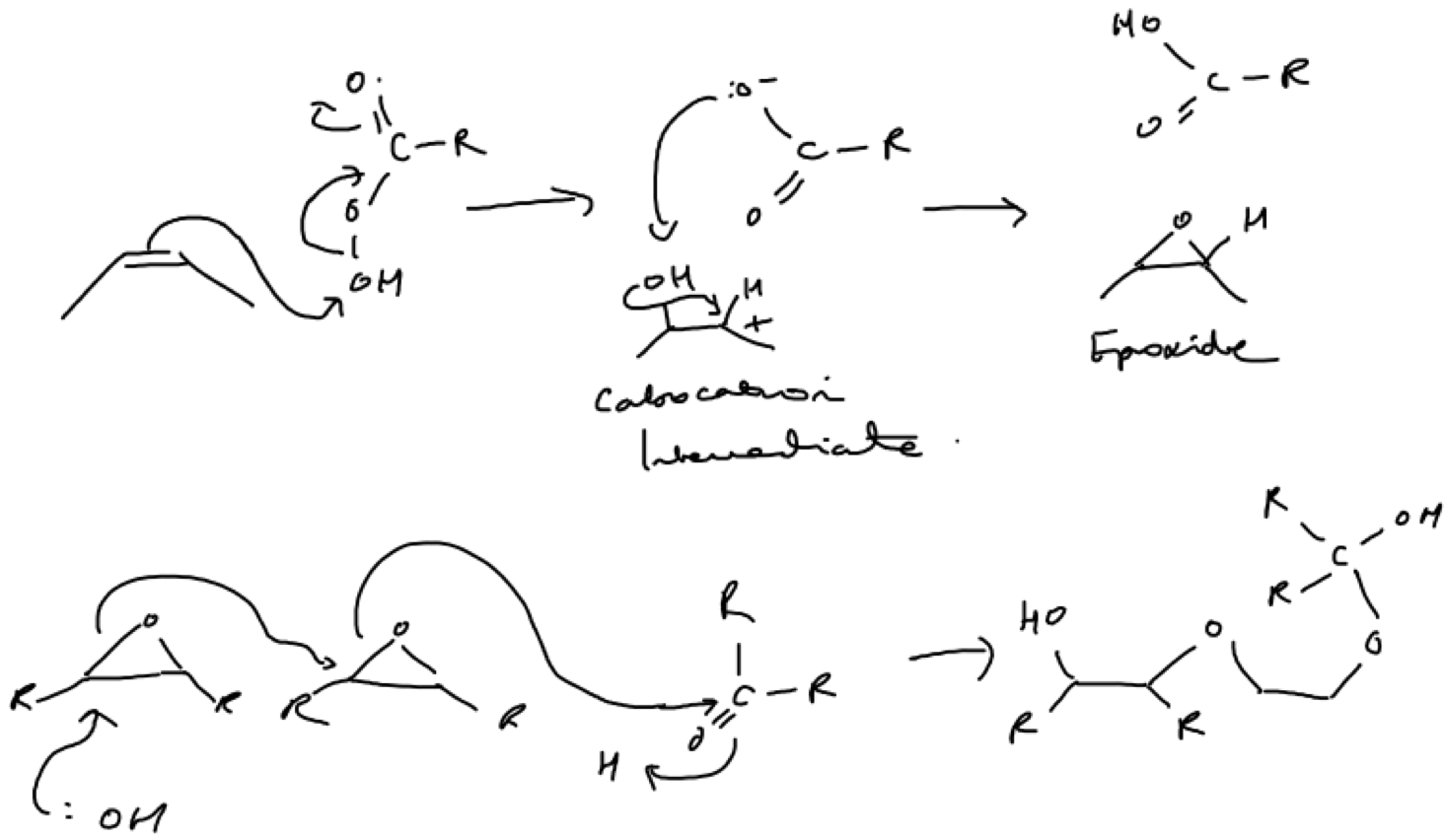

An epoxidation reaction generates a cyclic ether (e.g. from alkene and ester reactants: Fig.5; Lower). Furthermore, as cyclic ethers are unusually reactive nucleophiles by virtue of their strained geometry (in comparison to aliphatic ethers), long polyether chains can be generated through a series of epoxidation reactions (Fig.5; Lower).

Figure 5. Example of an epoxidation reaction (Upper mechanism). Here an alkene reacts with an ester to form a cyclic ether via a carbocation intermediate. You can see how the reaction could proceed in the reverse direction with the polyether being the nucleophile rather than the ether group (or how multiple cyclic ethers could be joined together as shown in the lower mechanism). I don’t know if this is a real mechanism but it appears plausible to me and from it you can see how more complex molecules can begin to emerge from the repetition of simple mechanisms.

Figure 5. Example of an epoxidation reaction (Upper mechanism). Here an alkene reacts with an ester to form a cyclic ether via a carbocation intermediate. You can see how the reaction could proceed in the reverse direction with the polyether being the nucleophile rather than the ether group (or how multiple cyclic ethers could be joined together as shown in the lower mechanism). I don’t know if this is a real mechanism but it appears plausible to me and from it you can see how more complex molecules can begin to emerge from the repetition of simple mechanisms.

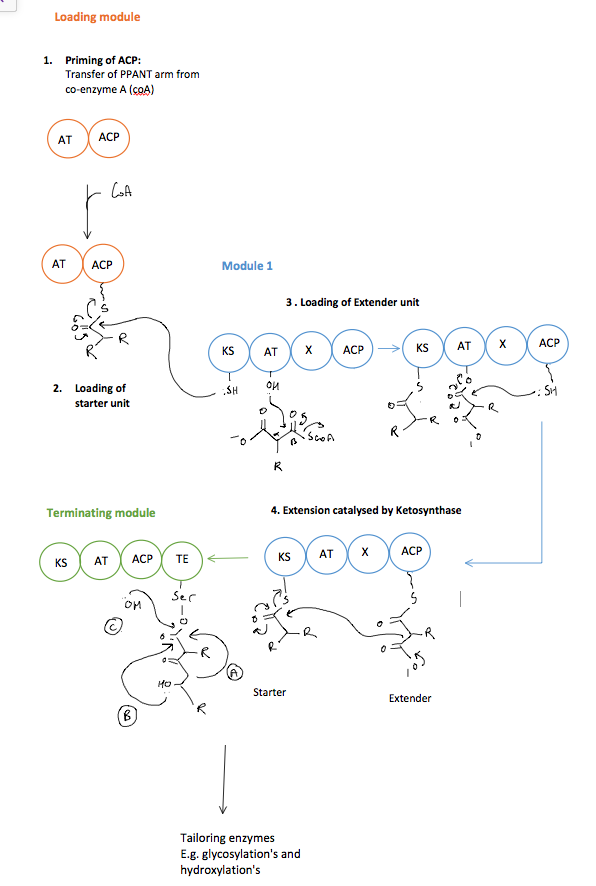

A minimal PKS assembly line

A minimal PKS module requires three essential enzymes arranged linearly; ketosynthase (KS) acyltransferase (AT) and ACP domains, with each module elongating the compounds chain further. The inputs into this assembly line are secondary metabolites from metabolic processes e.g. acetyl-coA and malonyl-coA are derived from the acetate pathway in lipid metabolism. A starter unit is loaded onto the loading module (module 0) and the extender unit is loaded onto the next module (module 1). These two units are then joined together and subsequently released from the PKS. This repetitive process forms long B-ketothioester chains (given the nomenclature beta because the keto group of the precursor is at the 2nd carbon from the carboxyl group).

Before one of the starter units can be loaded, the assembly line must be primed. It is also important to note that the following is the minimum number of domains required for a PKS (Fig.6). PKSs frequently contain additional domains e.g. methyltransferases and ketoreductases (ketone –> alcohol) in order to functionalise a compound further.

The below steps describe Fig.6:

- A long PPANT arm is transferred from co-enzyme A onto the ACP domain. This functions in mediating the transfer of the growing precursor between the different domains via transacylation reactions.

- The starter and extender units are loaded onto the AT domains of different modules via transesterification reactions (i.e. an ester is formed at the AT domain; RCOO-AT). The extender unit is transferred from the AT domain to the ACP domain and the starter unit is transferred from the AT domain onto the ACP domain and then subsequently onto the KS domain, all via transacylation reactions.

- When the starter and extender units are loaded onto the KS and ACP domains respectively, a claisen condensation reaction catalysed by the KS domain joins the two together with the expulsion of CO2.

- This loading and extension process is repeated depending on the number of modules (KS, AT, ACP) of the PKS. When the growing polyketide chain reaches the terminating module it is transesterified onto a thioesterase domain. Here the polyketide can be released from the PKS in a number of ways, most commonly by hydrolysis or cyclisation of the chain.

- Tailoring enzymes, not ‘bound’ to the PKS assembly line, can further functionalise the polyketide.

Figure 6. A minimal PKS assembly line. The transesterification of the starter unit is onto the ACP domain is not shown.

Figure 6. A minimal PKS assembly line. The transesterification of the starter unit is onto the ACP domain is not shown.

PKS example 1

Largely using the few mechanisms mentioned above we can build plausible retrosynthetic pathways for given polyketides. When a novel natural product is discovered, suggesting plausible retrosynthetic pathways guides initial experiments such as what precursor compounds to radioactive label. These feeding experiments followed by NMR can elucidate starter and extender compounds, rule out or ascertain specific mechanisms, and reveal the components of a PKS assembly line.

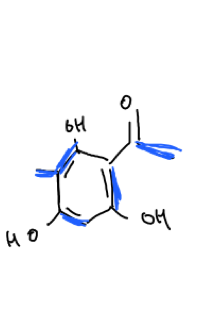

Consider the retrosynthesis of compound A in Fig.7. I don’t know the name of the compound, but this could be synthesised via the acetate pathway which yields the precursor acetyl-coA. From acetyl-coA we can also synthesise other building blocks such as malonyl-coA, butyryl-coA and methylmalonyl-coA to name a few.

The starter and extender units can be identified by annotating the compound (Fig.7). This compound can be synthesised from 1x acetyl-coA starter unit and 4x malonyl-coA extender units.

.

.Acetyl-coA is a product of the acetate pathway. An acetyl-coA carboxylase catalyses an aldol reaction between CO2 and acetyl-coA generate malonyl-coA via an enolate ion intermediate.

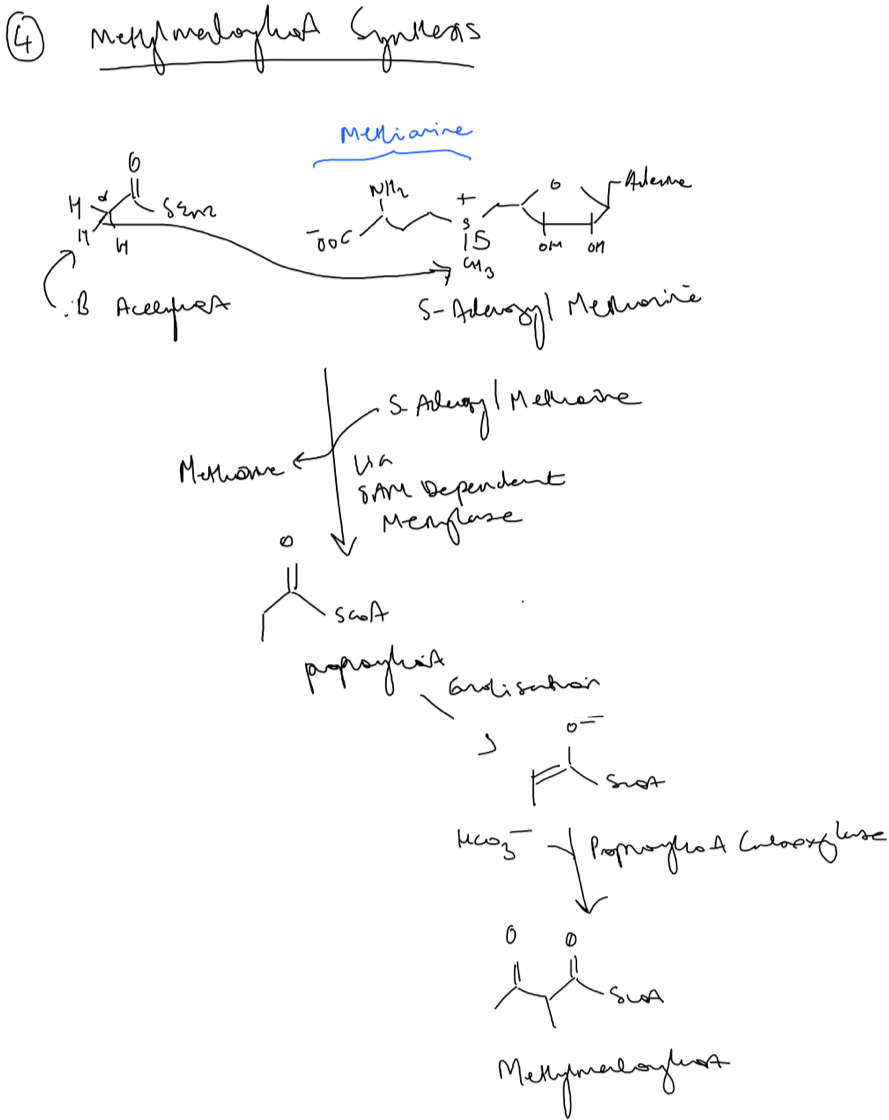

To synthesise methylmalonylcoA, a SAM dependent methylase adds a methyl group to acetyl-coA to generate propionyl-coA (Fig.9). Notice that the

leaving group in this reaction is the amino acid methionine. This is followed by the same aforementioned carboxylation dependent reaction to generate methylmalonlycoA. .

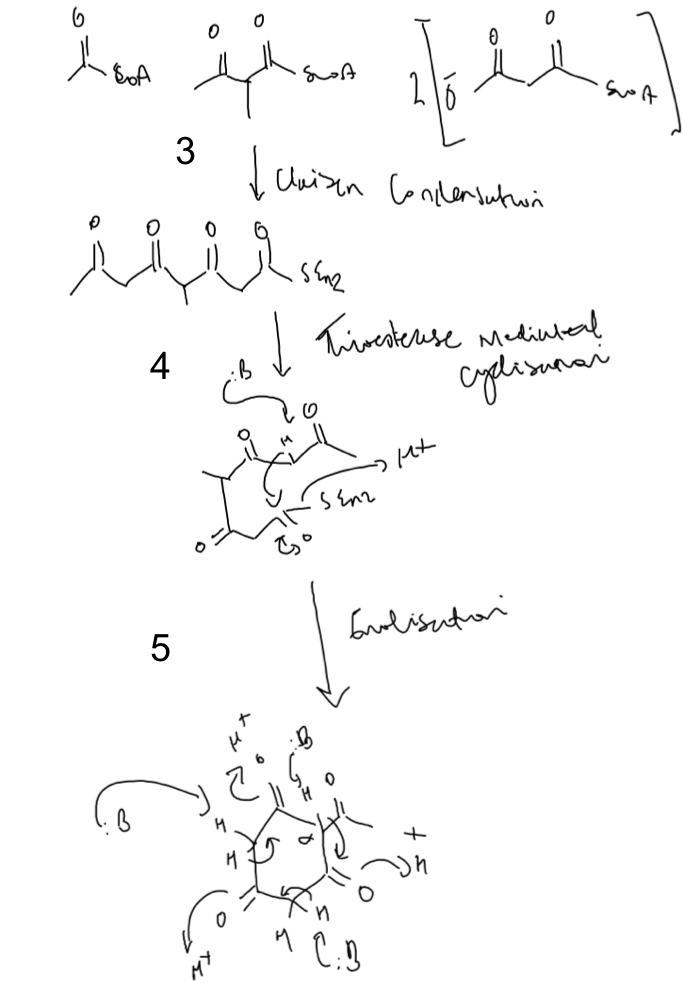

.- Numbering of the compounds ring identifies eight Cs, suggesting that the compound is formed from cyclisation of a tetraketide (There is a methyl group sticking out but this is a side chain of a precursor). Repeated claisen condensation reactions (catalysed by KSs) between the starter unit and the extender units yields this product (Fig.10; step 3).

- Next, we have to release the tetraketide form the PKS via the thioesterase domain. Deprotonation of the acidic hydrogens bound to the alpha-carbon creates a carboanion. This can act as a nucleophile in a nucleophillic acyl substitution reaction to cyclise the chain and concomitantly release the compound from the PKS (Fig.10; step 4).

A secondary cyclisation can now occur by tailoring - non PKS bound - enzymes. This could proceed via an enolisation reaction to generate the aromatic ring of compound A (Fig.10; step 5).

.

.

The above compound A could be synthesised by the shown method. There are also other routes for the synthesis of this compound. The methyl group that I added by forming methylmalonyl-coA could have also been added by a SAM dependent methyltransferase domain. This would be similar to Fig.9, although the nucleophile would be a double bond formed by enolisation. Based on the mechanisms above the components of this PKS would be a typical loading module (AT-ACP) followed by three KS-AT-ACP modules.

This post is getting quite long, so I am going to make a separate post on an interesting example of a PKS that is mentioned in the following papers; Chemistry of a Unique Polyketide-like Synthase, Biosynthesis of saxtoxin analogs: the unexpected pathway and Biosynthetic route towards saxitoxin and shunt pathway.

References

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_product#:~:text=Depending%20on%20the%20sources%2C%20the,ranges%20between%20300%2C000%20and%20400%2C000. [2] The Organic Chemistry of Biological Pathways by John McMurry